Henri Tuomilehto, MD; Hannu Kokki, MD; Riitta Ahonen, PhD; Juhani Nuutinen, MD

Ayman Ahmed Rabe Hussein Helal, *Department of health DOH -Abu Dhabi, UAE

ConferenceMinds Journal: This article was published and presented in the ConferenceMinds conference held on 27th Sep 2023 | London, UK.

PSIN : 0003376267 / HHW5289D/ 369H/ 2023 / 82HS532N / SEP 2023

Background:

Pain is a common complaint after ad-enoidectomy. Behavioral changes after adenoidectomy in children have been reported, and it has been concluded that postoperative pain significantly affects the occur-rence of behavioral changes. Behavioral changes, when a proactive pain treatment has been used, have not been systematically studied.

Objective:

To assess postoperative behavioral changes in children who have undergone day-case adenoidectomy with proactive pain treatment.

Design:

Prospective, longitudinal, randomized clinical trial.

Settings:

Ambulatory Care Unit, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland.

Patients:

Three hundred consecutive children, aged 1 to 10years, who underwent day-case adenoidectomy during 1999 through 2000.

Intervention:

In the hospital, 213 children received the first dose of ketoprofen before surgery and 87 children received the first dose at discharge. For pain treatment after discharge, patients were given ketoprofen tablets or suppositories on a regular basis for 72 hours.

Main Outcome Measures:

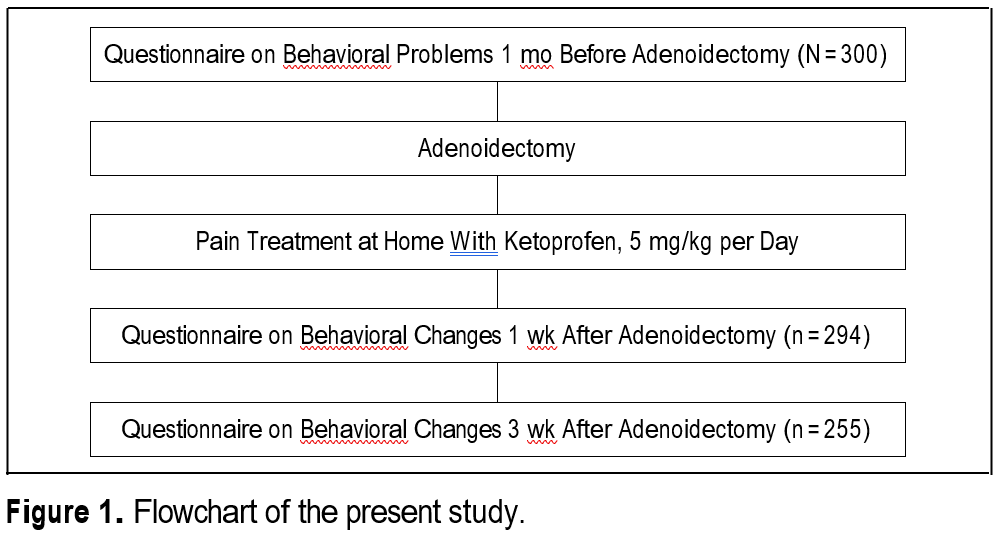

The number of postoperative behavioral changes were evaluated with 3 consecutive questionnaires, at baseline before surgery, 1 week after surgery, and 3 weeks after surgery.

Results:

A total of 294 questionnaires (98%) were returned after 1 week and 255 questionnaires (85%) after 3 weeks. Most children (91%) had pain after discharge and the mean for pain cessation was 3 days (range, 0-8 days). The mean of ketoprofen doses after discharge was 6 (range, 1-24 doses). Most of the children showed no or only trivial postoperative behavioral changes, and, furthermore, at 3 weeks, more positive than negative changes were reported. The child’s age was a significant factor (P, 0.5) in affecting behavioral changes for all domains. Other significant factors were the worst pain at rest (P=.04) and during swallowing (P=.02) for day-time function disturbances, and fear of separation from parents (P=.03) for sleep disturbances.

Conclusion:

Day-case adenoidectomy with proactive pain treatment seems to result in a negligible incidence of behavioral troubles in children.

DURING EARLY childhood, ear, nose, and throat procedures are the most common surgical operations, accounting, for example, in France, for up to two-thirds of operations in children younger than 4 years. Adenoidectomy is the most common day-case ear, nose, and throat procedure in many countries. In the Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland, approximately 500 day-case adenoidectomies are performed annually in children aged 1 to 7 years.

High-quality ambulatory surgery is a challenge for healthcare providers. The criteria for successful day-case service are minimal postoperative morbidity, a low in-patient admission rate, and high parental and child satisfaction. Achievement of these goals enables a calm recovery period with minimal need for contacting primary health care providers. Children respond psychologically to the prospect of surgery in a variable and age-dependent manner. Nonetheless, the surgical procedure and anesthesia have postoperative emotional sequelae on children, and may therefore result in a number of postoperative behavioral problems.

A recent study indicates that post-operative pain significantly affects the occurrence of behavioral changes in children. Pain is a common complaint after adenoidectomy. More than 50% of children experience pain after discharge and need analgesics at home. Because pain is perhaps the most poignant of all hospital fears, proactive pain treatment is advocated to allow for a peaceful recovery after surgery. On the other hand, some studies suggest that a well-organized day-case treatment of secretory otitis media, for example, improves children’s quality of life and reduces the demand for further use of health care services.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ketoprofen, are commonly used to treat mild and moderate pain and have proved to provide efficient analgesia with a low rate of adverse events in pediatric patients.

The present prospective clinical trial aimed to evaluate the incidence and severity of short-term postoperative behavioral changes in children aged 1 to 10 years who were given ketoprofen for proactive pain treatment after day-case adenoidectomy. We compared the magnitude of positive and negative behavioral changes at home 1 and 3 weeks after surgery with the findings before surgery.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

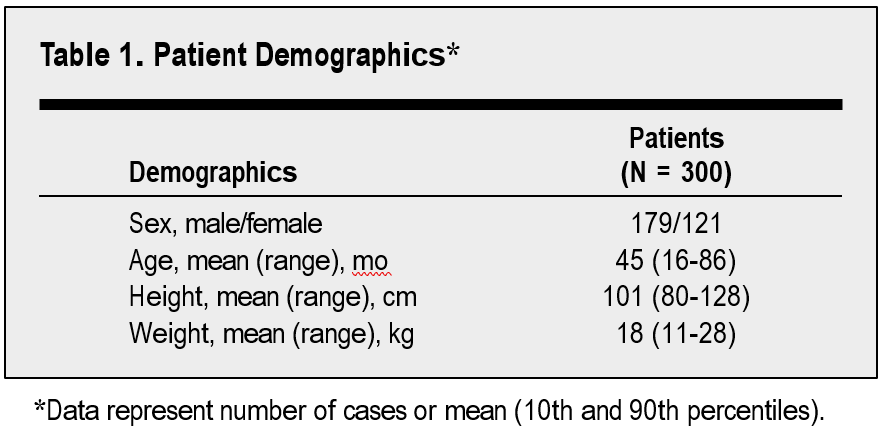

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kuopio University Hospital and was conducted in accordance with the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki. The National Agency for Medicines (Helsinki, Finland) was notified of the use of ketoprofen in children younger than 12 years. Both the parents and children old enough were informed, and written consent was obtained. This report is a part of a larger trial, and some other results of which have already been published. Our study comprised 300 consecutive children (179 boys and 121 girls) aged 1 to 10 years ( mean age, 3.8 years), American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status 1,undergoing day-case adenoidectomy during 1999 through 2000 in the Ambu-latory Care Unit of Kuopio University Hospital. Patients were excluded if they had a known allergy to ketoprofen or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, asthma, hemorrhagic diathesis, kidney or liver dysfunction, or had any other known contraindication for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs.

During the hospital stay, none of the children had any signs of an acute respiratory infection.

In the hospital, the trial, as a whole, was conducted in 3 stages differing in the administration routes of ketoprofen. Previously published parts of the study were prospective, randomized, double-blind, and double-dummy with a placebo control. In the present study, a total of 213 children received the first dose of ketoprofen before surgery and 87 children at discharge.

A similar endotracheal anesthesia was used for all children. Eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (EMLA) cream (Astra, So¨derta¨lje, Sweden) was used at the venous puncture site. Each child was premedicated with diazepam, 1 µg/kg of fentanyl citrate was given intravenously, and anesthesia was induced with thiopental sodium, intravenously. To facilitate tracheal intubation, cisatracurium besylate was given intravenously. Anesthesia was maintained with sevoflurane in nitrous oxide in oxygen with intermittent positive pressure ventilation. On completion of the procedure, muscle relaxation was reversed with administration of neostigmine bromide and glycopyrrolate.

The adenoids were removed using a curettage technique under visual control. Hemostasis was controlled with temporary nasopharyngeal packs and suction electrocautery, if needed.

After the operation, children were transferred to the postanesthesia care unit for continuous monitoring of vital signs and assessment of pain. In the postanesthesia care unit, if the child was in pain (a pain score at rest $3, on a 0-10 pain scale) fentanyl was given for rescue analgesia. No other analgesic medication was used during the 3-hour stay in the postanesthesia care unit.

Patients were discharged when they were awake, able to walk unaided, had stable vital signs for at least 1 hour, had no pain or only mild pain, had not vomited for 1 hour, were able to tolerate clear fluid by mouth, and had no bleeding. At discharge, all children were given 1 mg/kg of ketoprofen, intravenously.

At discharge, parents were instructed about the postoperative care of their child and pain management at home. A proactive pain treatment protocol was used at home with 5 mg/kg of ketoprofen per day, divided into 2 or 3 doses as tablets or suppositories. Medication was obtained by parents at dis-charge; parents were enforced to give the children ketoprofen on a regular basis for at least 72 hours after surgery and thereafter if needed. Parents were also given hospital contact telephone numbers in case of problems at home. All verbal information was reinforced with written instructions.

To evaluate the changes in the child’s postoperative behavior, the caregivers completed a questionnaire containing 24 items adapted from the Posthospital Behavioral Questionnaire modified by Kotiniemi et al. Data concerning the behavioral changes at home were collected at 3 consecutive times: on the day of operation before surgery, 1 week after the surgery, and 3 weeks after the surgery(Figure1). The first questionnaire was a retrospective evaluation of children’s behavior for a 1-month period before the operation. It also contained baseline data regarding demographics (eg, age, sex, weight, and height), disease status, family status, and family disease status.

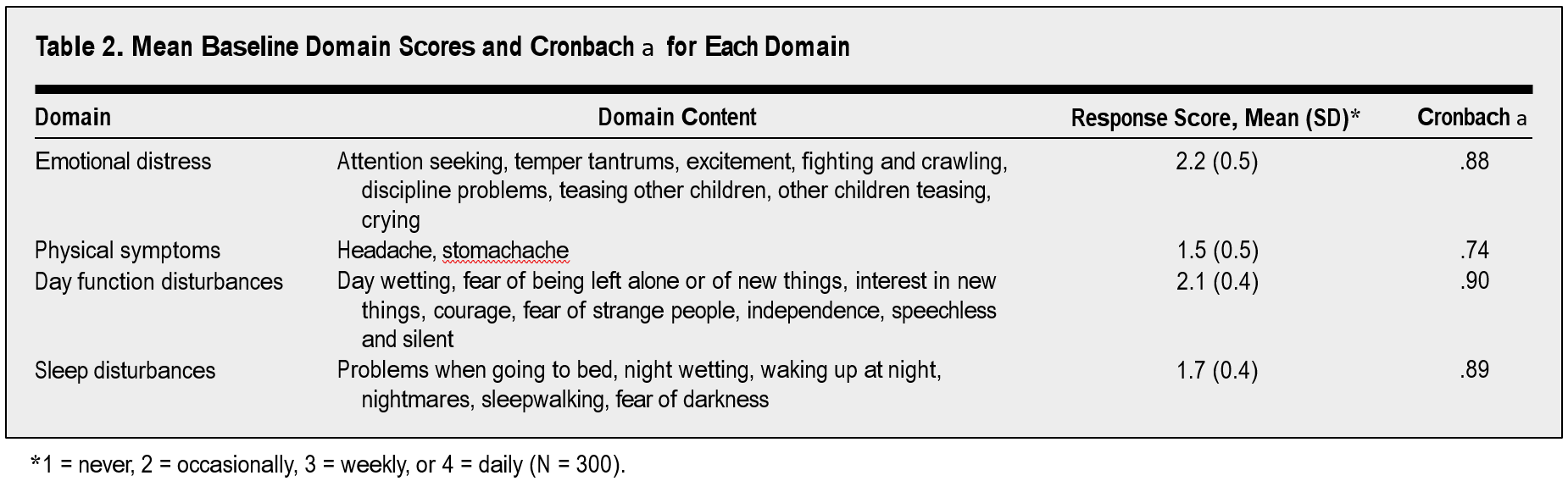

The items in the 3 questionnaires were divided into 4 domains: emotional distress, physical symptoms, daytime function disturbances, and sleep disturbances. In each of the 3 questionnaires, the caregivers rated the items on a 4-point scale (1=never, 2=occasionally, 3=weekly, or 4=daily). In the second and third questionnaires, parents were asked to compare each item with those for the previous data collection date (1=much less, 2=slightly less, 3=the same, 4=slightly more, or 5=much more). Thus, a higher score indicated a poorer outcome in both scales.

The baseline score for the 4 domains was calculated as a mean of the item scores, and the follow-up scores were similarly determined for the latter 2 questionnaires. Thus, a change score was calculated by subtracting the follow-up score from the score obtained at baseline (negative values reflect improved behavioral changes).

The second questionnaire, 1 week after surgery, consisted of questions about the intensity and duration of the pain experienced by the child at home, and about medication requirements and any adverseevents. At home, pain intensity was assessed using a 4-point verbal rating scale(1=no pain,2=mild pain, 3=moderate pain, or 4=severe pain).

A reminder letter was sent if either of the 2 latter questionnaires had not been returned in 6 weeks.

All statistical analyses were made using a statistical program (SPSS9.0;SPSSInc, Chicago,Ill). Change scores after surgery (1 week and 3 weeks) for each domain were compared with the scores obtained at baseline using repeated-measures analysis of variance. The internal consistency of the survey was assessed to determine reliability. The calculation of Cronbach a was used for the instrument as a whole and with removal of each domain. The reliability coefficient a greater than .70 was considered to be evidence of good reliability. The measure of agreement between 2 different rating methods was used to measure the change in postoperative behavior consecutively after 1 week and 3 weeks. Each domain was assessed by the Spear-man rank correlation test and the k test. A P value of less than .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results are presented as number (percentage) of cases, or mean (SD or range), as appropriate.

RESULTS

A total of 294 questionnaires were returned after 1week (responserate,98%) and 255 questionnaires after 3 weeks (response rate, 85%). The demographics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Pain after discharge was common, with 268 patients (91%) having pain at home. Most children had just mild or moderate pain; severe pain was reported in only 109 children (37%). The most intense pain occurred on the first postoperative day. The mean time for pain cessation was 3days(range,0-8days). A total of 285 children(97%) received ketoprofen at home, the mean number of doses was 6(range, 1-24doses). There was no difference between the children who received ketoprofen before or after surgery in time for pain cessation, number of analgesic doses administrated, or the intensity of pain at home.

The study demonstrated significant consistency, with a Cronbach a greater than .70 for all domains. Emotional distress and daytime function disturbances were the domains of greatest impact, followed by sleep disturbances and physical symptoms. The mean baseline survey responses and internal consistency with a Cronbach a for each domain are shown in Table2.

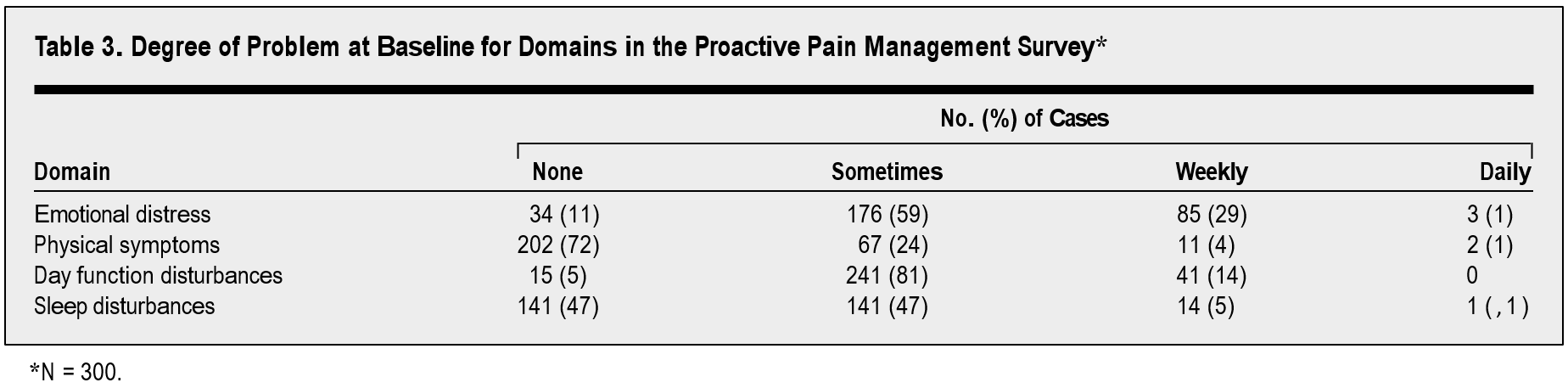

The extent of behavioral problems at baseline is shown in Table3. None of the children had any developmental disabilities or mental disorders. Overall, some minor behavioral disturbances were noted, but those are considered to be normal during childhood.

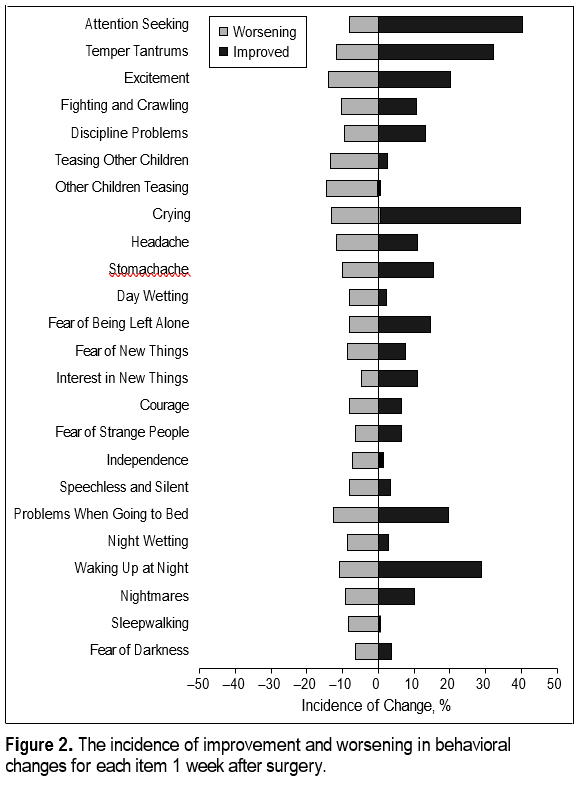

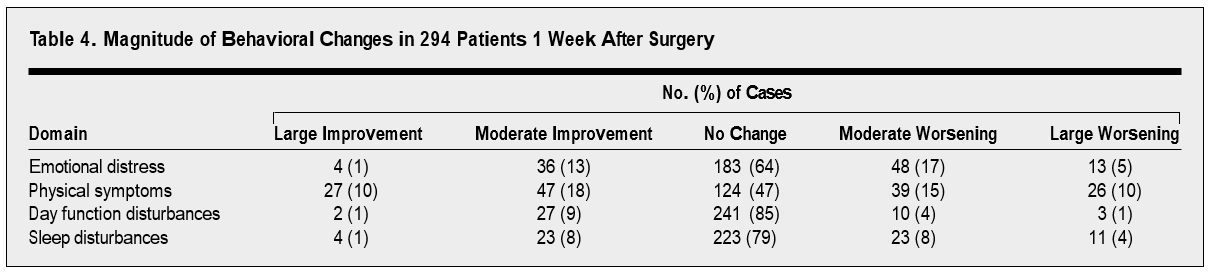

The change in postoperative behavior in the children was measured by subtraction of scores of consecutive questionnaires with the score obtained at baseline. One week after surgery, most children did not show any postoperative behavioral changes, and when changes were observed, they were equal in regard to improvements or worsening in any domain (1%-18%). Only a few chil-dren showed significant improvement or worsening in behavior after surgery. As expected, the largest degree of changes occurred in physical symptoms (ie, head-ache and stomachache) (Figure 2 and Table 4).

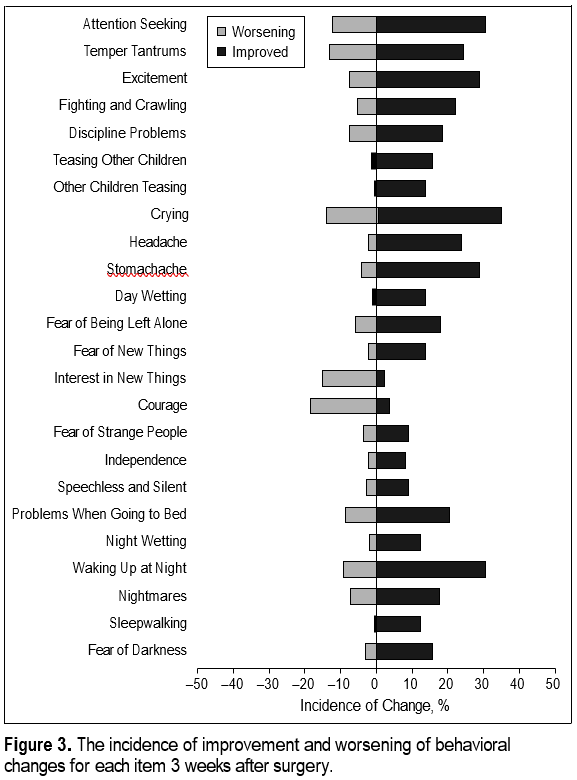

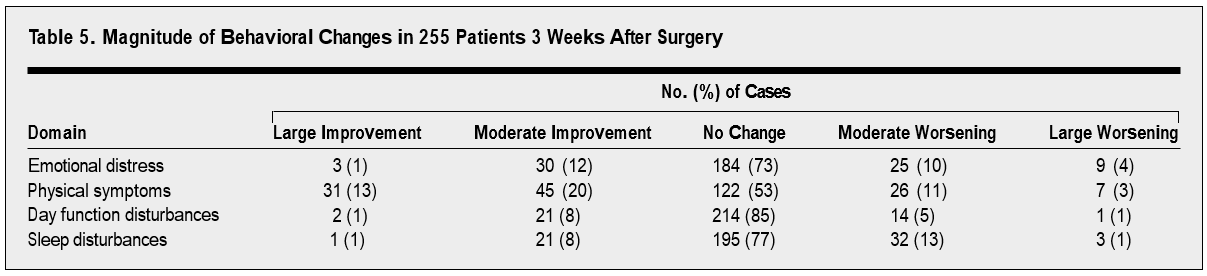

At 3 weeks after surgery, more positive than negative behavioral changes compared with the baseline were noticed, and only 1% to 4% of the children showed large worsening in any behavioral domain. However, most children did not show any behavioral changes (Figure 3 and Table 5).

The 2 different approaches in the questionnaires in measuring the changes in postoperative behavior—the 4-point incidence-rating and the comparable rating with baseline evaluation—were assessed by the Spearman rank correlation and the k tests. The 2 tests demonstrated a good correlation for each domain at both 1 and 3 weeks after surgery (P,.05 for each domain).

A general linear model test was used to evaluate factors affecting behavioral changes in the postoperative period. The age of the child was a significantfactor(P,.05) for all domains. Although differences were statistically significant, the actual changes in each domain during the follow-up period were rather minimal. Other significant factors affecting behavioral changes were the worst pain at rest (P=.04) and during swallowing (P=.02) observed in the postanaesthesia care unit for daytime function disturbances. Fear of separation from parents(P=.03) was a significant factor implicating sleep disturbances. The sex of the child had no effect on the results.

COMMENT

Behavioral changes are reported to be common after surgery in children, severe pain being one of the most significant factors. However, pain can be substantially reduced by appropriate management. It seems that the proactive pain treatment with ketoprofen performed well in the present study. Although many of the chil-dren had pain at home after adenoidectomy, it was mostly mild. Moreover, most of the children showed no or only trivial changes in their behavior postoperatively. Hence, we believe that an appropriate pain treatment regimen will help parents feel able to take responsibility for their children’s care after surgery, with a corre-sponding lower need for further contact with health care providers.

The present study was prospective and longitudinal but the results are observational because pain treatment at home was not placebo controlled. Concerning small children complaining of postoperative pain, the present form of trial settings mustbeacceptedforethicalrea-sons. Children experiencing moderate or severe pain should be provided effective analgesics. In our previous placebo-controlled studies we have shown that ketoprofen, a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug of the phenylpropionic acid group, has a significant analgesic effect in children after day-case surgery.

Besides pain, surgery and anesthesia constitute an emotional stress for children, and it is necessary to provide a child-friendly and child-safe environment, along with adequate pain management. Distraction techniques should be used to try to make the children and parents feel secure. We agree with Kain and colleagues that this will reduce negative postoperative behavioral changes in children. It seems that the treatment in our day-case unit was satisfactory, since most of the children showed no increase in emotional distress after surgery, and the changes noticed were equal in regard to improvements or worsening. Moreover, only a few children (1%-5%) showed any significant behavioral changes.

In the present study, physical symptoms (ie, headache and stomachache) were the most common complaints after surgery. This was expected because headache is a common symptom in children after throat surgery. Fear and excitement are known triggers for both stomachaches and headaches. Moreover, stomachaches and headaches are common during childhood; it has been found that half of the children in Finland have experienced a headache by the age of 7 years.

Good sleep is essential for children, and obviously disturbances in sleeping have consequences in the overall behavior of children. In previous studies, sleeping disturbances after adenoidectomy have been found to occur in 20% to 30% of children in the immediate postoperative period. However, in the present study, most of the children showed no change in sleep after surgery. Moreover, in those children who did show changes in their sleeping pattern, the changes observed were equal in regard to worsening and improvement. Only 12% and 14% of children had negative changes at 1 and 3 weeks after surgery, respectively.

The effect of disease itself on behavioral problems cannot be underestimated, and it has been shown that an improvement in the child’s medical condition has a beneficial effect on the quality of life. Rosenfeld and colleagues evaluated the effect of surgical procedures on children’s postoperative behavioral changes, and found that the insertion of tympanostomy tubes improves the children’s subjective well-being and,therefore,their quality of life. In the present study, children with acute respiratory infections, which would have worsened the situation even more, were excluded, according the hospital’s surgical protocol.

In a recent study, Kotiniemi and colleagues5 detected a substantial incidence of problematic behavioral changes in children 1 week after minor ambulatory surgery. The significant factors predicting problematic changes in behavior after surgery were severity of postoperative pain, age of child (more negative changes were observed among children, 3years),andapreviousbad experience with health care. In the study by Kotiniemietal, the incidence of problematic changes decreased from 47% to 9% during a 4-week follow-up, but at the same time, the frequency of beneficial changes decreased from 17%to9%. Inourstudy, where we used a proactive pain treatment, the incidence of worsening in behavioral domains was lower and the incidence of improvements was higher than reported by Kotiniemi et al.

Parents’guidance is essential in children’s pain management at home. Giving appropriate and clear instructions to caregivers improves the quality of pain management at home. We believe that the approach used in the present study, where parents were instructed about proactive pain treatment and where all verbal information was reinforced with written instructions, supported the parents in using pain medication in a regular and proper manner. An adequate postoperative pain treatment is a part of the quality program of the Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care and Department of Otorhinolaryngology. In this respect, a constant quality control of the pain management directory is essential.

Four of 5 children experience pain at home af-ter adenoidectomy, and significant pain lasts for 2 to 3 days. Because the worst pain after adenoidectomy occurs on the first postoperative day, parents should be instructed to continue regular pain medication on arrival at home to avoid an unwanted breakthrough of pain.

In conclusion, pain in children after day-case ad-enoidectomy is common. Proactive pain treatment is advisable. The incidence of significant behavioral problems is rare.

Accepted for publication March 11, 2002.

This study was supported by the Erityisvaltionosuus grant (5551805) from Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland.

The study was conducted in collaboration with the University Hospital of Kuopio and the University of Kuopio.

Corresponding author and reprints: Henri Tuomilehto, MD, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kuopio University Hospital, PO Box 1777, FIN-70211 Kuopio, Finland (e-mail: henri.tuomilehto@kuh.fi).

REFERENCES

- Clerque F, Auroy Y. French survey of anesthesia in 1996. Anesthesiology. 1999; 91:1509-1520.

- Kokki H, Ahonen R. Pain and activity disturbances after pediatric day case ad-enoidectomy. Paediatr Anaesth. 1997;7:227-231.

- Brennan L J. Modern day-case anesthesia for children. Br J Anaesth.1999;83:91-103.

- McGraw T. Preparing children for the operating room: psychological issues. Can

J Anaesth. 1994;41:1094-1103. - Kotiniemi LH, Ryha¨nen PT, Moilanen IK. Behavioural changes in children following day-case surgery: a 4-week follow-up of 551children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:970-976.

- Wolf AR. Tears at bedtime: a pitfall of extending pediatric day-case surgery without extending analgesia. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:319-320.

- Scaife JM, Johnstone JMS. Psychological aspects of day care surgery for children. In: Healy TEJ, ed. Baillier’s Clinical Anesthesiology. Vol 4. London, En-gland: Baillier Tindall; 1990:760-771.

- Rosenfeld R, Bhaya MH, Bower CM, et al. Impact of tympanostomy tubes on child quality of life. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:585-592.

- Nikanne E, Kokki H, Tuovinen K. IV perioperative ketoprofen in small children during adenoidectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1997;78:24-27.

- Morton NS. Prevention and control of pain in children. Br J Anaesth. 1999;83: 118-129.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 52nd World Medical Association, General Assembly; October 2000; Edinburgh, Scotland.

- Tuomilehto H, Kokki H, Tuovinen K. Comparison of intravenous and per oral ketoprofen for postoperative pain after adenoidectomy in children. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:224-227.

- Kokki H, Tuomilehto H, Tuovinen K. Per rectum pain management after adenoidectomy with ketoprofen: comparison of rectal and intravenous routes. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:836-840.

- Tuomilehto H, Kokki H. Parenteral ketoprofen for pain management after adenoidectomy: comparison of intravenous and intramuscular routes of administration. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2002;46:184-189.

- Maunuksela EL, Olkkola KT, Korpela R. Measurement of pain in children with self-reporting and behavioral assessment. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;18:407-414.

- Kain ZN, Wang SM, Mayes L, Caramico LA, Hofstadter MB. Distress during the induction of anesthesia and postoperative behavioral outcomes. Anesth Analg. 1999;88:1042-1047.

- Kotiniemi LH, Ryha¨nen PT, Valanne J, Jokela R, Mustonen A, Poukkula E. Postoperative symptoms at home following day-case surgery in children: a multi-centre survey of 551 children. Anaesthesia. 1997;52:963-969.

- Aromaa M, Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Rautava P, Helenius H. Childhood headache at school entry. Neurology. 1998;50:1729-1736.

- Sillanpa¨a¨ M, Anttila P. Increasing prevalence of headache in 7-year-old school children. Headache. 1996;36:466-470.

- Sepponen K, Ahonen R, Kokki H. The effects of a hospital staff training program on the treatment practices of postoperative pain in children under 8 years. Pharm World Sci. 1998;20:66-72.

- Nikanne E, Kokki H, Tuovinen K. Postoperative pain after adenoidectomy in children. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:886-889.