Abstract

Over the past several decades, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) has become the routine treatment for a number of hematological disorders (e.g., leukemia, lymphoma), as well as treatment for some autoimmune diseases and inherited metabolic disorders.1,2 One possible complication after stem cell transplantation is graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), an inflammatory condition that can affect many different organs, including the eyes. Ocular manifestations of GVHD are common and can significantly decrease quality of life. Without a basic understanding of ocular GVHD, the condition can be challenging to diagnose and adequately treat. This report summarizes the basics of HCT and ocular GVHD, and gives an example case of ocular GVHD treated with scleral lenses.

Keywords: Graft – verse – host disease, autoimmune disorders, keratoconjunctivitis sicca,

Case Report

A 57-year-old Caucasian female, presented to the University of Virginia eye clinic on April 2018 for a contact lens evaluation. She had been referred, with a diagnosis of severe dry eye disease, secondary to ocular GVHD. The patient had a history of acute myeloid leukemia, now in remission after undergoing an allogeneic (matched sibling) bone marrow transplant in 2000.

The patient’s chief complaint during the initial visit was irritation in both eyes (OS>OD) starting in May 2017, which manifested as a “burning and gritty” sensation, redness, tearing, and light sensitivity. She reported that these symptoms had been gradually worsening since their onset and were now constant in duration. Her treatment included preservative-free artificial tears PRN (>6x/day per patient) OU, daily warm compresses OU, erythromycin ointment QHS OU, doxycycline PO 100mg/day, punctal plugs OU, and serum tears with Restasis QID OU, which had been prescribed prior to her visit. On slit lamp examination, we found that a punctal plug was in place in the left eye only.)

In addition to irritation in both eyes, the patient reported mild blurry vision at all distances. She had undergone cataract surgery in both eyes in 2005. She did not wear any correction for distance and used +2.50 OTC readers for near. She had ocular hypertension, for which she took Cosopt BID OU and Xalatan QHS OU. Other medical history included gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Uncorrected distance visual acuity was 20/30-2 OD and 20/50+2 OS, with pinhole improvement to 20/25-2 OD and 20/25+2 OS. Intraocular pressures were 14mmHg OD and 17mmHg OS. Testing of pupils, extraocular muscle movement, and counting fingers visual fields was normal.

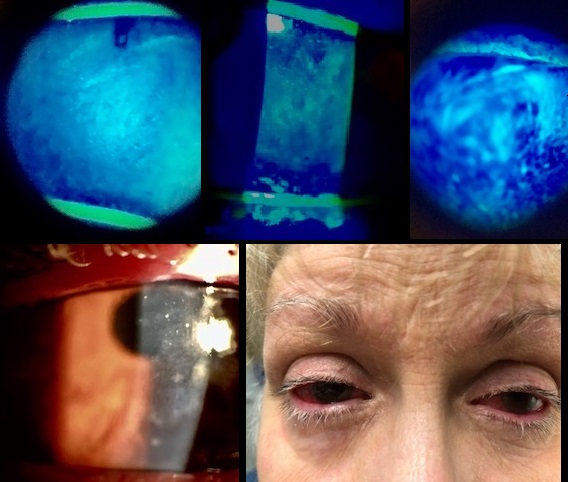

Slit lamp examination revealed poliosis of the eyelashes, 1-2+ capped meibomian glands, trace scurf, telangiectasia, tyalosis, and distorted gray lines (per lissamine staining) in both eyes. There were diffuse punctate epithelial erosions, diffuse subepithelial infiltrates, and conjunctival injection in both eyes (see Figure 1). Per the grading scales outlined in the International Chronic Ocular GVHD Consensus Group report, the patient had grade 3 corneal fluorescein staining and grade 2 conjunctival injection.7

Figure 1. Clockwise from top: Grade 3 (severe) corneal fluorescein staining, Grade 2 (severe) conjunctival injection, Subepithelial infiltrates.

Diagnosis:

Ocular GVHD has no clinical signs or symptoms that are specific for the disease.1 Patients often present with typical dry eye symptoms such as a gritty or foreign body sensation, burning, itching, tearing and/or redness.1 Medical history is important to the diagnosis of ocular GVHD.

In 2013, the International Chronic Ocular Graft-Versus-Host Disease Consensus Group provided new diagnostic metrics for chronic ocular GVHD.7 Their report identified four subjective and objective variables to measure in patients following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: (1) Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI), (2) Schirmer’s score without anesthesia, (3) Corneal staining, and (4) Conjunctival injection.7 Each variable is scored 0-2 or 0-3, with a maximum composite score of 11 (see Table 1).7 The report provided representative images of corneal staining and conjunctival injection at different levels of severity to help with scoring.7 Altogether, a diagnosis of ocular GVHD considers the total score, as well as the presence or absence of systemic GVHD.7

| Table 1: Severity scale in chronic ocular GVHD | ||||

| Severity scores

(points) |

Schirmer’s test (mm) | CFS

(points) |

OSDI

(points) |

Conj

(points) |

| 0 | >15 | 0 | <13 | None |

| 1 | 11-15 | <2 | 13-22 | Mild/Moderate |

| 2 | 6-10 | 2-3 | 23-32 | Severe |

| 3 | ≤5 | ≥4 | ≥33 | |

| CFS: Corneal fluorescein staining; Conj: Conjuctival injection

Total score (points) = (Schirmer’s test score + CFS score + OSDI score + Conj score) Severity classification: None: 0-4, Mild/Moderate: 5-8, Severe: 9-11

|

||||

Adapted from Ogawa, et al.7

| Table 2: Diagnosis of chronic ocular GVHD | |||

| None

(points) |

Probable GVHD

(points) |

Definite GVHD

(points) |

|

| Systemic GVHD (-) | 0-5 | 6-7 | ≥8 |

| Systemic GVHD (+) | 0-3 | 4-5 | ≥6 |

*Adapted from Ogawa, et al.7

We did not complete Schirmer’s test without anesthesia at the time of the patient’s visit. The wetting length should be increased without anesthesia. While we expect she would have had values in the moderate to severe range, we have chosen to be conservative and give her a severity score of 0 for Schirmer’s.8 The patient had severity scores of 3 for corneal fluorescein staining, 3 for OSDI, (detailed in the next section), and 2 for conjunctival injection. A total score of 8 generated a severity classification of mild/moderate (see Table 1). According to the International Chronic Ocular GVHD Consensus Group, our patient had “Definite GVHD” whether or not you consider her GERD a systemic manifestation of GVHD (see Table 2).

To quantify our patient’s symptoms prior to the scleral contact lens fitting, the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) Questionnaire was use. The OSDI is a 12-item questionnaire designed to provide an assessment of the symptoms of dry eye disease (DED) and their impact on vision-related functioning.9 The OSDI is scored on a scale of 0-100, with higher scores representing greater disability.9 Our patient had a final score of 90.9 indicating severe DED.

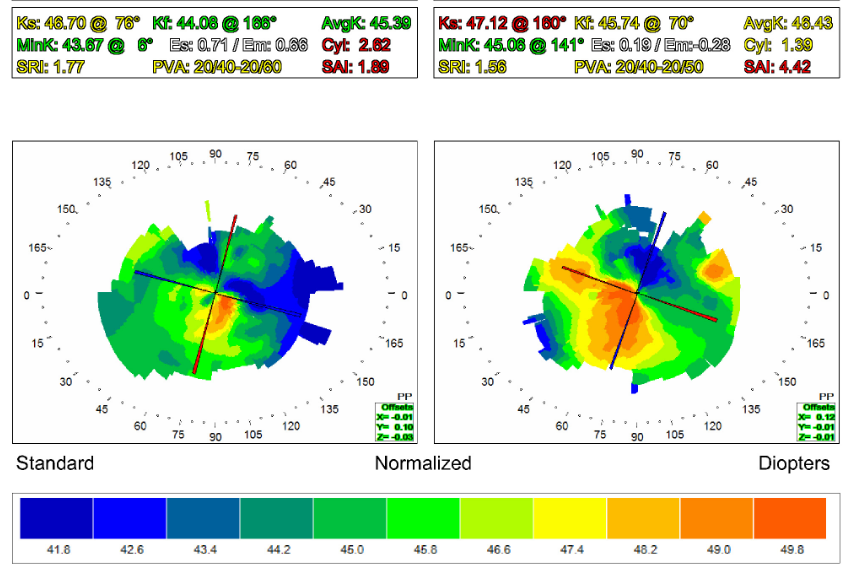

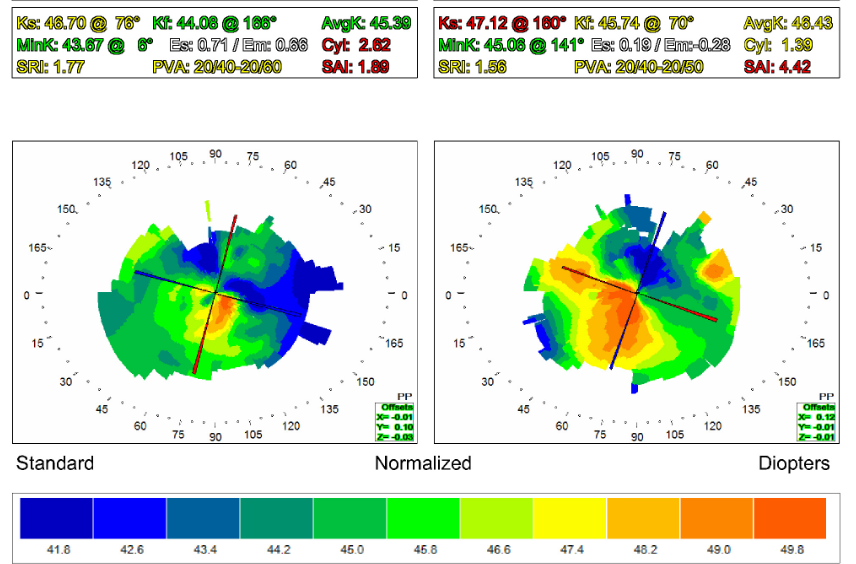

We took a baseline topography using standard Topcon topographer (see Figure 2). This topography showed mild to moderate irregular astigmatism. No defined pattern could be identified. Both factors were probably a result of severe ocular surface dryness. Corneal curvature was slightly increased.

Figure 2. Topography results.

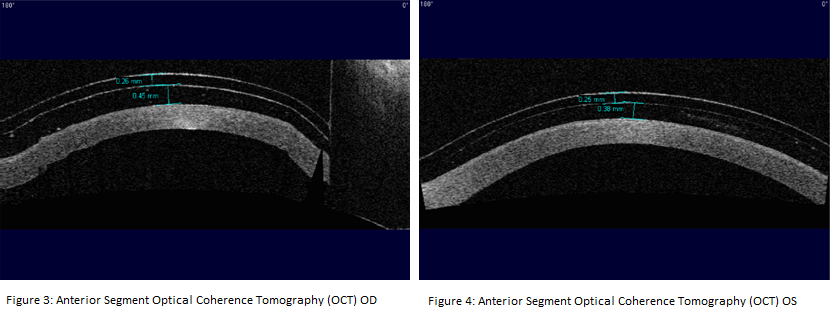

The patient was fitted in Onefit 2.0 scleral lenses with a central corneal clearance of 380 ± 110 um.3 These lenses provided vaults of 450um OD and 380um OS (see Figure 3) after ten minutes of wear time. We assumed that the lenses would lose some central corneal clearance (≤ 100um) over the first hour with settling.10

Discussion

HCT involves an intravenous infusion of healthy stem cells that have been harvested from a patient’s own tissue (autologous) or from human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-matched donor tissue (allogeneic). In an allogeneic HCT, stem cells are taken from bone marrow, peripheral blood, or umbilical cord blood.1 The goal of the treatment is to incite an immune response against malignant cells and to restore hematopoietic function.3 When using HLA-matching between non-identical donors and recipients, there are often genetic differences outside of the HLA region, in the form of minor histocompatibility antigens.1 As a consequence, approximately 40 to 60% of patients receiving allogeneic HCT develop GVHD.1

GVHD is a multisystem disorder that arises when immune cells transplanted from a donor (the graft) recognize proteins on cells of the recipient (host) as foreign, thereby causing an exaggerated immune reaction and a multitude of complications. GVHD has historically been divided into acute and chronic. Definitions of the acute and chronic variants are based on specific tissue involvement instead of time of onset.3 Acute GVHD (aGVHD) affects multiple organs – primarily the skin, liver, and intestinal tract – and can be fatal.3 Chronic GVHD (cGVHD) is more complex in presentation, with manifestations similar to autoimmune disorders such as Sjogren syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis.1, cGVHD causes fibrosis, stenosis, and atrophy of tissues in the skin, lung, and mucous membranes., including the eyes.4 A large majority of patients with cGVHD have suffered from previous episodes of aGVHD.4 The risk factors for cGVHD are not fully understood, but it is thought that gender and donor to recipient ages play a role.1,3

Ocular GVHD is a general term for keratoconjunctivitis sicca, conjunctival disease, and other ocular surface issues following allogeneic HCT.1 Ocular complications have been reported in roughly 40 to 60% of patients after transplantation, as compared with non-ocular complications in 60 to 90% of patients.1, 2 The presence of skin and/or mouth involvement puts patients at a higher risk for ocular involvement. Ocular involvement can be the first manifestation of systemic GVHD2 and may be associated with greater GVHD severity.1, 3 Ocular GVHD can significantly impair a patient’s quality of life and restrict activities of daily living. The condition warrants close ophthalmic monitoring and treatment.

Ocular tissues affected by acute and chronic GVHD include: the eyelids and periorbital skin, lacrimal system, cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, lens, uvea, and retina.2 The most common manifestation of ocular GVHD is dry eye disease (DED), otherwise known as keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), which typically occurs 6 to 12 months after stem cell transplantation.1 The primary cause of cGVHD-related KCS is lacrimal gland dysfunction with severe aqueous deficiency, a process that appears to be associated with lymphocytic infiltration.1,3 T-cells and other inflammatory cells often target the mucous membranes lining of the ducts of major and accessory lacrimal glands and meibomian glands.1,4

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca related to cGVHD is often exacerbated by meibomian gland dysfunction, and is less often worsened by lid dysfunction, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy.4 When severe, KCS can lead filamentary keratitis, neovascularization, neurotrophic keratopathy, ulceration, and corneal melting.4 Other ocular complications associated with GVHD include: cataracts that are commonly posterior subcapsular opacities, microvascular retinopathy, central serous chorioretinopathy, posterior scleritis and vitritis.3,4 It is important to note that the cataracts and posterior segment findings reported in cases of GVHD may be adverse effects of pharmacologic therapy rather than GVHD.3,4

Interest in scleral lenses has grown considerably in the past several years. Most patients with ocular GVHD have a normal scleral contour, making the process of fitting scleral lenses on these patients relatively straightforward. Fitting should be followed with quantifiable measures, such as OSDI. GVHD has the potential to cause severe ocular problems in allogenic HCT, impairing quality of life. Therefore it is essential to perform close ocular monitoring of these patients.

here are no known preventative therapies for ocular GVHD.1 Treatments for this condition are aimed at protecting the eyes from further damage and providing long-term symptomatic relief.3 The treatment strategies include improving tear function and decreasing ocular surface inflammation. Eye care providers typically use a “stepped care” approach, starting with the simplest forms of therapy and increasing the aggressiveness of their intervention as necessary.3

The first step of treatment include patient education and counseling;2 The frequent use of preservative-free and phosphate-free artificial tears during the day, and a viscous lubricating ointment at bedtime.1,3 If the meibomian glands are involved, warm compresses (for ten minutes at least twice a day) and optimal lid hygiene (e.g. lid scrubs) should be encouraged.1,3 Environmental management includes the avoidance of tobacco smoke, ceiling fans, electric heaters, etc. and the installation of humidifiers.2,3 For some patients, these treatments are enough to maintain comfort. For others, further treatments are required.

The next step in treatment is punctal occlusion with collagen (temporary) or silicone (permanent) plugs to inhibit tear drainage and sustain lubrication of the ocular surface.1,3 Researchers have previously posed the concern that retention of tears may increase the concentration of inflammatory factors on the eye and therefore cause more harm than benefit.3 Studies now have shown that punctal plugs are beneficial.3 If punctal plugs provide symptomatic relief without causing epiphora, or if repeated plug loss occurs due to abnormal lid anatomy, thermal cauterization of one or all four puncta can be considered.1,3

Topical anti-inflammatory drugs can also be used when managing ocular GVHD. Cyclosporine A (0.05% or 0.1%) inhibits T-cell activation, down-regulates release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and increases goblet cell density.1 It is initiated twice a day, but can be administered more frequently.1 Topical corticosteroids are another treatment option.1 However, corticosteroids are contraindicated if the patient suffers from corneal epithelial defects, stromal thinning, infiltrative keratitis, and/or infectious keratitis.1

Autologous serum eye drops, derived from the patient’s own blood serum, mimic natural tears more closely than artificial tears and contain valuable nutrients such as epithelial growth factors, nerve growth factor, inhibitory cytokines, vitamin A, and fibronectin.1,3 Autologous serum provides good lubrication and promotes corneal and conjunctival healing.1,3 These properties can make autologous serum an optimal treatment for ocular GVHD, but the production of autologous serum eye drops is a complex process, limited to specialized centers, and costly.1,3

If a patient remains symptomatic after exhausting all of the cited treatment options, eye care providers can consider contact lenses. Contact lens treatment may rigid gas-permeable scleral lenses (proprietary PROSE treatment from Boston Foundation for Sight or other commercially available designs).1,3 Scleral lenses have been shown to provide symptomatic relief and can help protect the cornea from the frictional forces of blinks and the external environment, scleral lenses are generally considered the superior treatment option.1,3 Scleral lenses rest on the conjunctival tissue overlying the sclera and completely vault the cornea and limbus. Consequently, they create a tear reservoir between the lens and the ocular surface, which provides continuous hydration of the cornea and a sustained oxygen supply.1 Scleral lenses also mask ocular surface irregularities, which can improve the quality of vision. As with any conventional contact lens wear, eye care providers must consider increased risk of infection. This is an especially important consideration if the ocular GVHD patient has active epitheliopathy or is taking immunosuppressant therapy.3

Surgical intervention may be necessary in severe cases of ocular GVHD, if all other therapies fail to provide symptomatic relief. These interventions include superficial epithelial debridement and/or amniotic membrane transplantation to promote corneal healing, and tarsorrhaphy to reduce ocular surface exposure.1,3 While tarsorrhaphy has its advantages, it is important to educate patients that the procedure will limit his or her peripheral vision and may complicate the insertion of therapeutic contact lenses.3 As last resorts, an eye care providers may consider limbal stem cell transplantation or penetrating keratoplasty; however, unsurprisingly, corneal transplantation is carries a high risk in patients with ocular GVHD.1

Conclusion

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in patients who have undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. This condition can affect multiple organ systems and therefore requires close monitoring and care by a multidisciplinary team of doctors. Ocular manifestations are common, eye care providers should expect to be a part of these treatment teams. There are multiple strategies at our disposal to tailor our management plan to each individual patient. Scleral lenses are one such strategy that has been found to provide both symptomatic relief and ocular surface protection for patients with ocular GVHD.3

We report a patient who presented with severe DED due to cGVHD following allogeneic HCT. By her account and by OSDI questionnaire, this severely impaired her quality of life and restricted her daily activities. Scleral lenses restored much of both and made her eyes “feel normal again.”

Bibiolography

- Munir SZ, Aylward J. A review of ocular graft-versus-host disease. Optom Vis Sci 2017; 94(5): 545-55.

- Nassiri N, Eslani M, Panahi N, et al. Ocular graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplantation: A review of current knowledge and recommendations. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2013; 8(4): 351-58.

- Balasubramaniam SC, Raja H, Nau CB, et al. Ocular graft-versus-host disease: A review. Eye Contact Lens 2015; 41(5): 256-61.

- Nassar A, Tabbara KF, Aljurf M. Ocular manifestations of graft-versus-host disease. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2013; 27: 215-22.

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005; 11(12): 945-56.

- Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. The 2014 diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015; 21(3): 389e1-401e1.

- Ogawa Y, Kim SK, Dana R, et al. International Chronic Ocular Graft-vs-Host Disease (GVHD) Consensus Group: Proposed diagnostic criteria for chronic GVHD (Part I). Sci Rep 2013; 3: 3419.

- Li N, Deng X, He M. Comparison of the Schirmer I test with and without topical anesthesia for diagnosing dry eye. Int J Ophthalmol 2012; 5(4): 478-81.

- Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, et al. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol 2000; 118: 615-21.

- Otchere H, Jones L, Sorbara, L. Effect of time on scleral lens settling and change in corneal clearance. Optom Vis Sci 2017; 94: 908-13.